PHNOM PENH, Sept. 23, 2025 — A simmering border conflict between Cambodia and Thailand, reignited on May 28, 2025, is threatening the 58-year-old ASEAN bloc and raising fears that prolonged hostilities could undermine the region’s hard-won stability.

The clashes, marked by Thai military aggression against Cambodian civilians, have expanded into Cambodia’s northwestern provinces, casting doubt on ASEAN’s credibility as a community built on cooperation, trust and a zone of peace.

Cambodian Prime Minister Hun Manet has sounded the alarm to world leaders including Presidents Donald Trump and Xi Jinping, warning that the conflict has spread beyond the disputed border areas of Preah Vihear and Oddar Meanchey into other provinces.

“In his letters, Samdech Thipadei Hun Manet apprised these world leaders on the chain of events that led to the widening of the conflict zone … and urged full respect for the ceasefire terms and agreements reached at recent General Border Committee (GBC) and Regional Border Committee (RBC) meetings,” Cambodia’s Foreign Ministry said in a Sept. 17 statement.

The ministry added that since 12 August, Thai forces have widened the conflict zone by erecting barbed wire and barricades, issuing ultimatums, and forcibly evicting Cambodian civilians from long-settled lands in Chouk Chey and Prey Chan villages of Banteay Meanchey Province. “Twenty-five families have already been blocked from their homes and fields, and Thai military spokespeople recently threatened further evictions … potentially affecting hundreds of households,” it said.

Citing “credible sources,” Prime Minister Hun Manet said Thai forces plan to seize territory at 17 other sites stretching from Pursat to Koh Kong Provinces. Cambodia denounced these actions as unilateral moves based on Thailand’s self-drawn maps, branding them attempts to suppress a smaller neighbor with fewer resources.

Even more troubling, on September 18, 2025, on Sept. 18, 2025, the Spokesperson of the First Military Region of the Royal Thai Army issued a public warning on the application of Thai domestic law against Cambodian nationals, which includes the imposition of penalties up to life imprisonment or even the death penalty for so-called “acts against Thai sovereignty.” This followed incidents on September 17, 2025, where Thai security forces used tear gas and rubber bullets against Cambodian villagers in Prey Chan Village, where Thailand recently used force in an attempt to exert territorial sovereignty.

For decades, ASEAN has promoted the vision of “One Community.” But when two members exchange artillery fire, the bloc’s non-interference principle leaves it paralyzed—unable to act decisively and risking its image as a united family.

While Cambodia has appealed to the U.N. Security Council, the International Court of Justice, and major powers including the United States and China, Thailand insists the matter should remain bilateral. ASEAN frameworks like the Treaty of Amity and Cooperation and the ASEAN Charter have so far proven ineffective.

The use of F-16 jets, drones, and heavy artillery by Thai troops has already led to civilian casualties and mass displacements in Cambodia. Observers warn the violence could tarnish ASEAN’s reputation as a zone of peace and stability, raising doubts about its ability to safeguard its Political-Security Community and maintain investor confidence.

Instead of advancing economic integration, infrastructure projects, or the South China Sea Code of Conduct, ASEAN leaders may now find themselves consumed by preventing escalation between Phnom Penh and Bangkok. Analysts caution that prolonged distraction could slow regional progress and allow external powers to exploit internal divisions.

Trade and tourism between Cambodia and Thailand have already been disrupted. Rising nationalist sentiment is straining cross-border relations and undermining ASEAN’s drive for deeper people-to-people ties.

The crisis has renewed debate over ASEAN’s conflict-management capacity. Without stronger mechanisms, analysts say, the bloc risks losing its claim to “centrality” in regional security. Yet some argue the Cambodia-Thailand clashes could serve as a wake-up call, forcing ASEAN to strengthen institutions and recommit to peaceful dispute resolution.

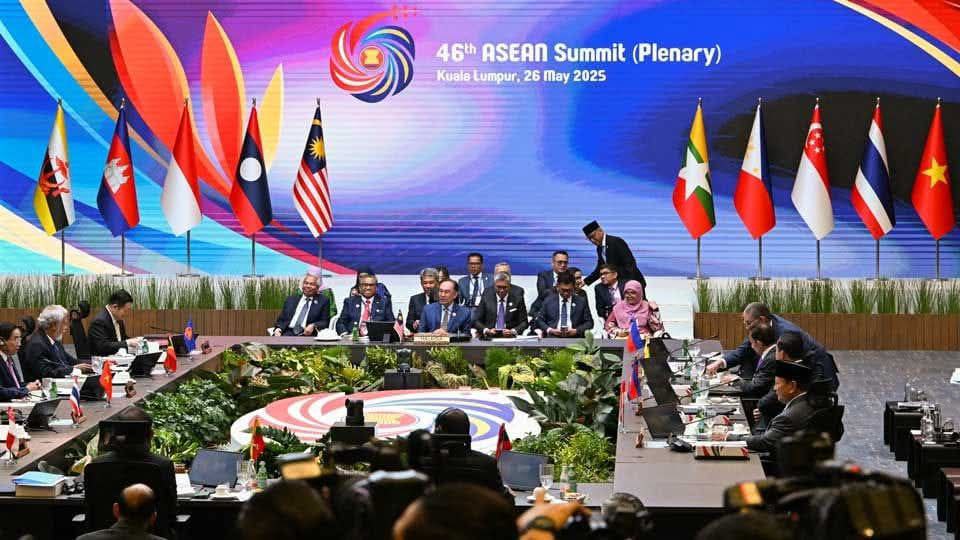

All of the above concerns should be brought into the upcoming ASEAN summit and related gatherings of the world’s leaders in Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, in the coming weeks. But given the uncertainty of the dual power structure in Thailand’s political system—between the government and the military—how should ASEAN engage with Thailand? And should it consider treating Thailand as a “second Myanmar” under military rule?

Author: Puy Kea, President of the Club of Cambodian Journalists